Far Out Distant Sounds, in conjunction with Maybe Mars, has put together an exhibition of Chairman Ca’s iconic poster art at Melbourne, Australia’s The Old Bar on February 21. The exhibition contains seventeen sets of signed and numbered prints spanning the past decade and will be followed with performances by White+, JP Shilo, and Xiao Zhong. Keep reading for more on the artist and his connection to the Chinese underground scene.

Text by Michael Pettis and Josh Feola

Certain music scenes are associated indelibly with the works of particular artists. In the mid-1960s, Robert Crumb’s surreal comics, posters, and album covers comprised the visual representation of the psychedelic San Francisco music scene. Over a decade later, Jamie Reid’s situationist posters and ransom-note album covers visually defined the London punk scene. The trinity was completed with Zhan Shihao, better known as Chairman Ca, leader of roughly a dozen young artists and comic book designers who banded together under the name Cult Youth Collective.

Chairman Ca was one of the young Beijing artists eager to make sense of two or three of the most transformative decades experienced by any country in history. Starting around 2005 for nearly a decade these artists unleashed in Beijing a wildly creative music scene that signaled the beginning of a new culture of urban Chinese youth. As a close friend of many of the period’s most important young musicians, and sharing their values and their sophisticated but coarse Beijing humor, Chairman Ca’s wild, anarchic drawings so completely expressed the voracious exuberance of the Beijing music scene that it has become impossible to imagine the latter except in terms of Ca’s images.

It is important to understand the cultural background of these artists. China has changed so dramatically in the past three decades that it is not just foreigners who stumble over stereotypes. China’s urban youth culture evolved out of uniquely Chinese conditions, but because it sidesteps all the traditional China stereotypes, it is easy for grumpy elders, wary government officials, and well-meaning Westerners to dismiss this new culture as “foreign” or subversive.

The conditions that transformed China over a few decades from a country that was 75 percent rural to one that is predominantly urban are well known: income up more than twenty times, soaring inequality, dozens of the world’s largest cities springing up overnight, crowding together hundreds of millions of former villagers. But other, less obvious conditions have been just as important. With parents who came of age in a society wracked by the Cultural Revolution, the “little emperors” who grew up in one-child China face a generation gap like that of their American baby-boom counterparts but one which, although perhaps less confrontational, is far deeper.

Where their parents set conformity and security as the main priorities for their children, these seemed irrelevant to many intelligent and sensitive young Chinese coming of age in a money-obsessed society. During the late 1990s, like young Americans trouping to New York’s Greenwich Village or San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury nearly four decades earlier, the more adventurous among them congregated in the cheap hutong districts of Beijing and other newly-cosmopolitan cities, fed up with mainstream Chinese culture and uncertain of their own ambitions, but determined to figure them out.

As they invented their new lives, with signposts often little more than garish Western style magazines, they began piecing together ways for Chinese artists to use Western forms along with older Chinese ideas to create art that was more than just a rejection of the mainstream culture of their parents. In the first few years of the new millennium, young China experienced a seismic cultural shock when it got online and the musical and artistic floodgates suddenly opened. Chinese musicians and artists for the first time had unfiltered access to a century’s worth of cultural movement from around the world, and as history flattened out a whole new attitude developed among them.

The cultural impact of the internet was electrifying. Young Chinese tore ecstatically through musical and artistic ideas, grabbing at anything that intrigued them, with no thought of genre, no worry about context and no sense of history. Visual artists, musicians, cartoonists, fashion designers, filmmakers and students grabbed onto this intensely Chinese way of experiencing modern music and art, at once deeply international and, with an artistic education stripped of historical context, uniquely Chinese.

Perhaps because this is such a rich way to experience art, from then on cultural tastes developed at breakneck speeds. Within a very few years a group of young Beijing musicians, schooled in punk, German electronica, New York No Wave, American Minimalism and free jazz, combined with the schmaltzy pop culture and kitschy ethnic music propagated by CCTV and other mainstream media during their childhood, and steeped in the love of texture and melodic structure typical of Chinese music, banded together to set off a half-dozen years of what is already seen as a golden age for the Beijing music underground. They put on shows, mainly for each other, at the tiny What Bar, perched provocatively at the edge of the Forbidden City, and then moved en masse to D-22, the music dive that they made famous.

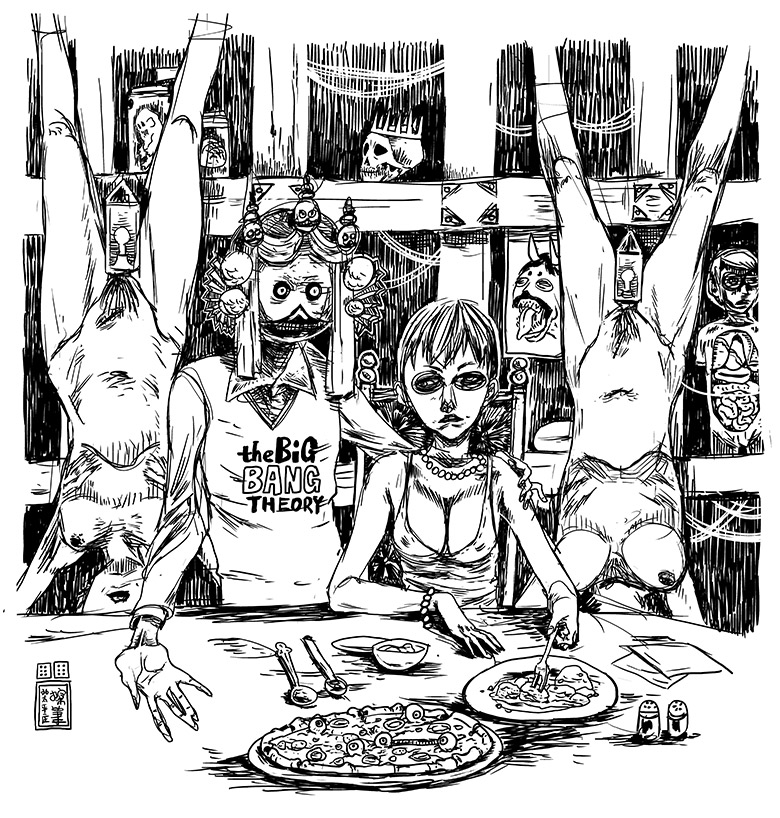

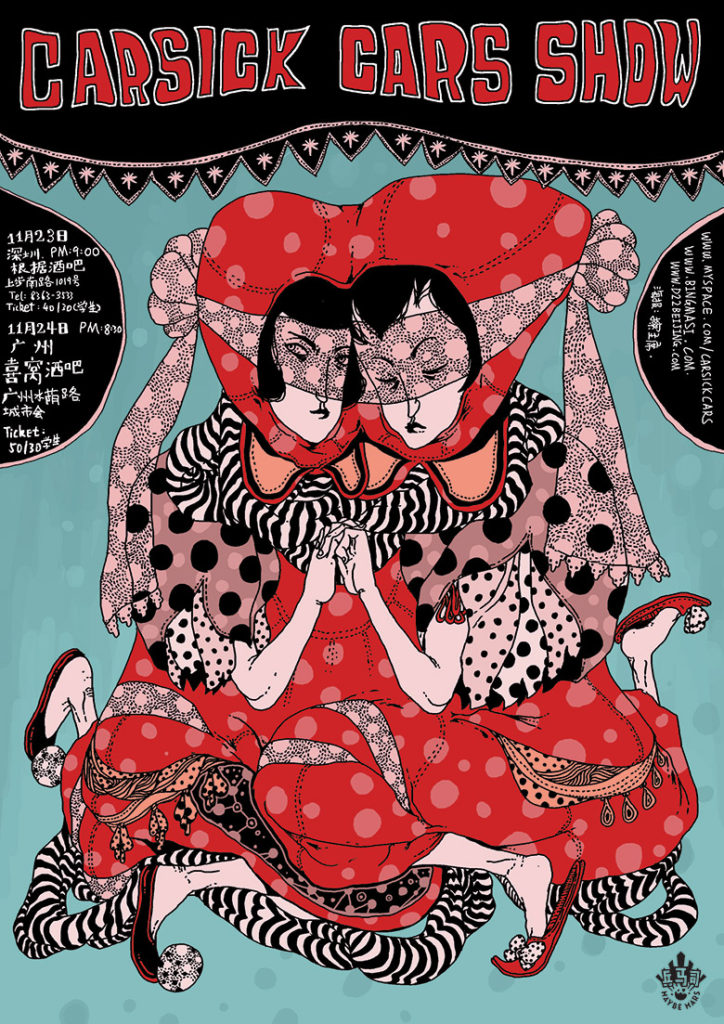

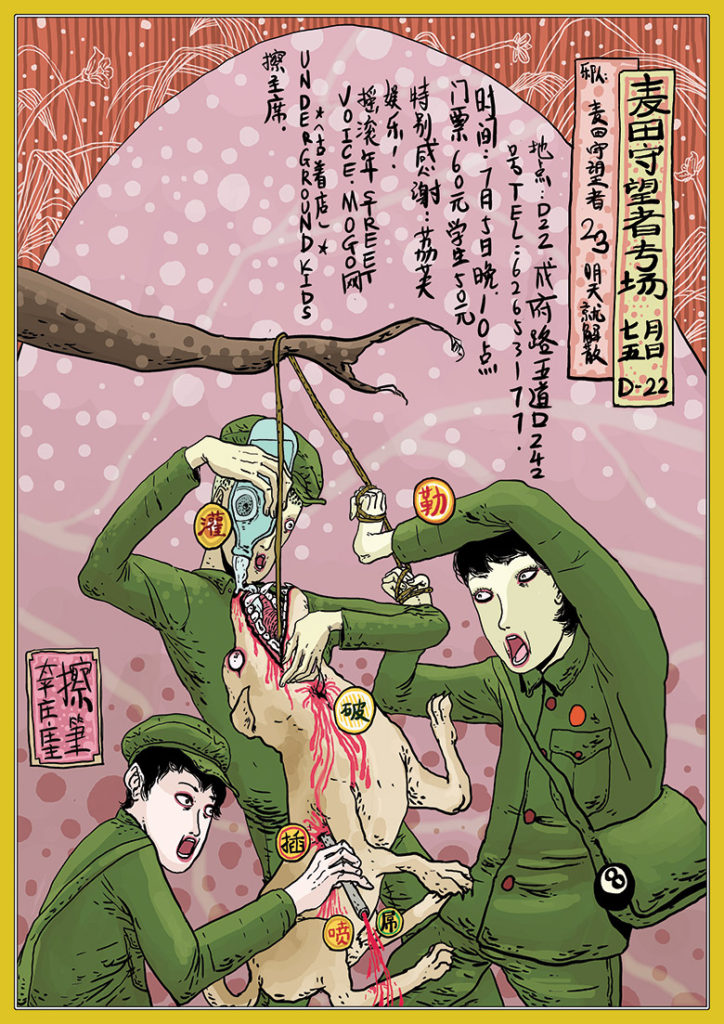

From the very beginning, Chairman Ca was a part of this movement. Combining the gaudy Chinese visual culture of the 1980s with which he grew up and the Japanese manga and American comics over which he pored obsessively, he traded with the musicians DVDs of American and Japanese monster flicks, of cheap Monkey King cartoons, and of Hong Kong kung fu or triad thrillers. From the beginning, the venue D-22 chose him to create his magnificent posters and flyers advertising performances by early torchbearers of the underground music scene like Joyside, P.K.14, Carsick Cars, Ourself Besides Me, Snapline, and other now-legendary bands that emerged from the club. D-22 even famously had him design and paint its grotty bathrooms.

Ca’s works, from the level of the mural down to the gig handbill, express an entire imagined universe of disaffected youth in transition. His style is “cartoonish” in both an avant-garde and lowbrow sense, belonging in a pantheon including Crumb and Ed Roth, Roy Lichtenstein and Takashi Murakami, and a legion of anonymous Hentai masters. In the early D-22 days, Ca’s prolific poster art was like an id projection of the club’s rough-and-ready regulars: degenerate rockabillies and half-rotted zombies; tentacular, clawed and spiked humanoids pulled from darkest regions of the post-nuclear pulp manga imagination; cackling old men in pajamas smoking cigarettes in narrow Beijing hutongs; three-eyed tigers and six-breasted women; all in various states of undress, degradation, death and decomposition. His work, taken together, presents a fabulist and phantasmal, stream-of-consciousness narrative of Beijing’s early 2000s sex-drugs-and-rock’n’roll revolution, a cultural matrix where young punks are elevated to the level of deities and demons, espousing a value system invented on the fly and based primarily on a loud, visceral rejection of their parents’ culture.

Over time, Ca’s work has expanded to incorporate more elements of Chinese and foreign kitsch, and to cover more media. In his latest dense illustration work, you’re as likely to see one of his trademark rockabilly zombies or a Beijing prostitute as you are to see a sideshow freak, a motorcycle outlaw, or a Mexican luchador draped in S&M gear. Ca has spent the last several years developing a series of vinyl toys and figurines that bring his menagerie into the third dimension, and bring his essentially childlike creative vision into a mature, adult phase.

What is Chairman Ca’s art, ultimately? In many ways he is doing exactly what his friends in the music scene are doing. When you have grown up to see your city change at breakneck pace, constantly being broken up and reconfigured with influences from everywhere and everything, it becomes a natural way of thinking about art. In Beijing everything is unfinished: constructions holes with dirty pools of water are situated right next to pretentious buildings that house fashionable restaurants with expensive decoration, usually in awful taste, filled with a bewildering assortment of unrecognizable objects, all of this overlooking the inevitable traffic jams on an adjacent highway.

In that sense Chairman Ca’s fascination with every kind of Chinese and foreign influence and the way he picks up and drops things at lightning speed makes him the perfect visual counterpart of the Beijing music. He has grabbed whatever he likes from the modern and contemporary art traditions of the rest of the world, with a great deal of love but with no respect, and he has forged them into his own cultural background as a young man growing up in rapidly changing China. He takes visual ideas from San Francisco’s underground comics, from Maoist posters, from Japanese manga, from New York Pop Art, from European surrealism, from old Shanghai advertisements, and forces them to conform to his experience of China in the 1990s.

But for all his international sophistication, whenever you see Chairman Ca’s posters and drawings you are immediately aware that he is, above all, a Beijinger. His work displays a cynical, dirty, inner-city hutong humor special to the Chinese capital, a sensibility that grows in narrow shadowed streets and walled courtyards, smirks at tragedies, makes fun of the powerful, and finds the shit in the emperor’s underwear.

Chairman Ca’s art is so tied up with the music and ideas of the young Beijing art scene, and are so familiar to all of us who have participated in that scene, that his comics, posters, CD covers, drawings and designs will always be the image of Beijing’s underground at the beginning of the 21st Century. Listen to the music, wander the loud, dirty streets of Beijing, and see the pictures in this show. These images will be icons 100 years from now.

Don’t miss the exhibition at The Old Bar on Tuesday February 21.